How the use of Artificial Intelligence should be regulated is a topic that is currently being debated fiercely. Many concerns on the possible ramifications of AI, ranging from ethics to economics and how the government should prevent the consequences, are being discussed globally.

One complication of AI has gained traction along with rising anxiety on Earth’s declining health: AI’s impact on the environment.

When AI models are integrated into large businesses’ existing infrastructure, they are often stored in data centers. These AI data centers can occupy up to 1 million to 2 million square feet and house a notable amount more technologies than other centers, such as cloud data centers, which take up around 100,000 square feet.

The United Nations Enviromental Programme (UNEP) found in their report Navigating New Horizons, which examined AI’s environmental footprint, that these data centers hurt the planet.

One problem with the centers is that the electronics they house depend on a staggering amount of matter. One 2 kg computer requires 800 kg of raw materials, such as palladium, copper, cobalt, and other rare earth materials (REEs). Additionally, the microchips that power AI rely on REEs.

The extraction of these materials is often environmentally destructive and causes soil erosion, loss of biodiversity, soil contamination, and other adverse effects.

Data centers also produce electronic waste, which contains mercury and lead. These substances are neurotoxins that can have many negative health effects on humans and can affect a child’s development. When released through electronic waste, they contaminate the air and fresh water.

AI-related infrastructure needs a lot of water during construction and operation. Water is often used to cool down the electronics that are constantly working, although the alternative technique of air circulation exists. As AI continues to grow, data centers are becoming more dense with technology, so more water is being used to facilitate the cooling process.

According to one report, AI-related infrastructure globally is estimated to soon consume six times as much water as Denmark, home to 6 million people. The study also estimates that about 10 to 50 responses from GPT-3 consume a half-liter of freshwater.

The United Nations (UN) estimates that 2 billion people, around a quarter of humanity, lack access to safe drinking water. AI’s water consumption can worsen prolonged droughts in water-stressed regions, such as Arizona and Chile.

Data centers demand a significant amount of energy to host AI technologies. AI is rapidly evolving, and more models are being trained. Training a model uses a lot of energy. When a model is being trained, data is being run through a model thousands of times, meaning that thousands of chips work for thousands of hours, consuming thousands of megawatts of energy. Every new generation of graphic processing units (GPU), the chips used to train AI models, require more energy than the previous generation.

Sarah Luccioni, lead climate researcher at an AI company called Hugging Face, says, “They’re [new GPUs] more powerful, but they’re also more energy intensive….It’s kind of this vicious circle. When you deploy AI models, you always have to have them on. ChatGPT is never off.”

Luccioni calculates in her own research that an AI generative approach to a task uses 30 to 40 times more energy than to another approach to the same task.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), one request made through ChatGPT uses 10 times the energy of a Google Search. The IEA also estimates that AI models’ energy consumption will roughly equal Japan’s in 2026.

The amount of energy required for each model needs a reliable source that renewable sources, such as solar and wind, that depend on the weather and other environmental factors cannot provide. The energy used for the centers frequently comes from the burning of fossil fuels, which releases greenhouse gases, a cause of global warming and local air pollution. The training process of a single AI model emits hundreds of tons of carbon.

However, AI does have some positive effects on the environment. For example, an AI-run smart home could reduce a household’s CO2 consumption by up to 40%. A recent Google study discovered that pilots can be guided to flight trails that leave the fewest contrails by AI quickly crunching atmospheric data. Contrails are around a third of the aviation industry’s contribution to global warming.

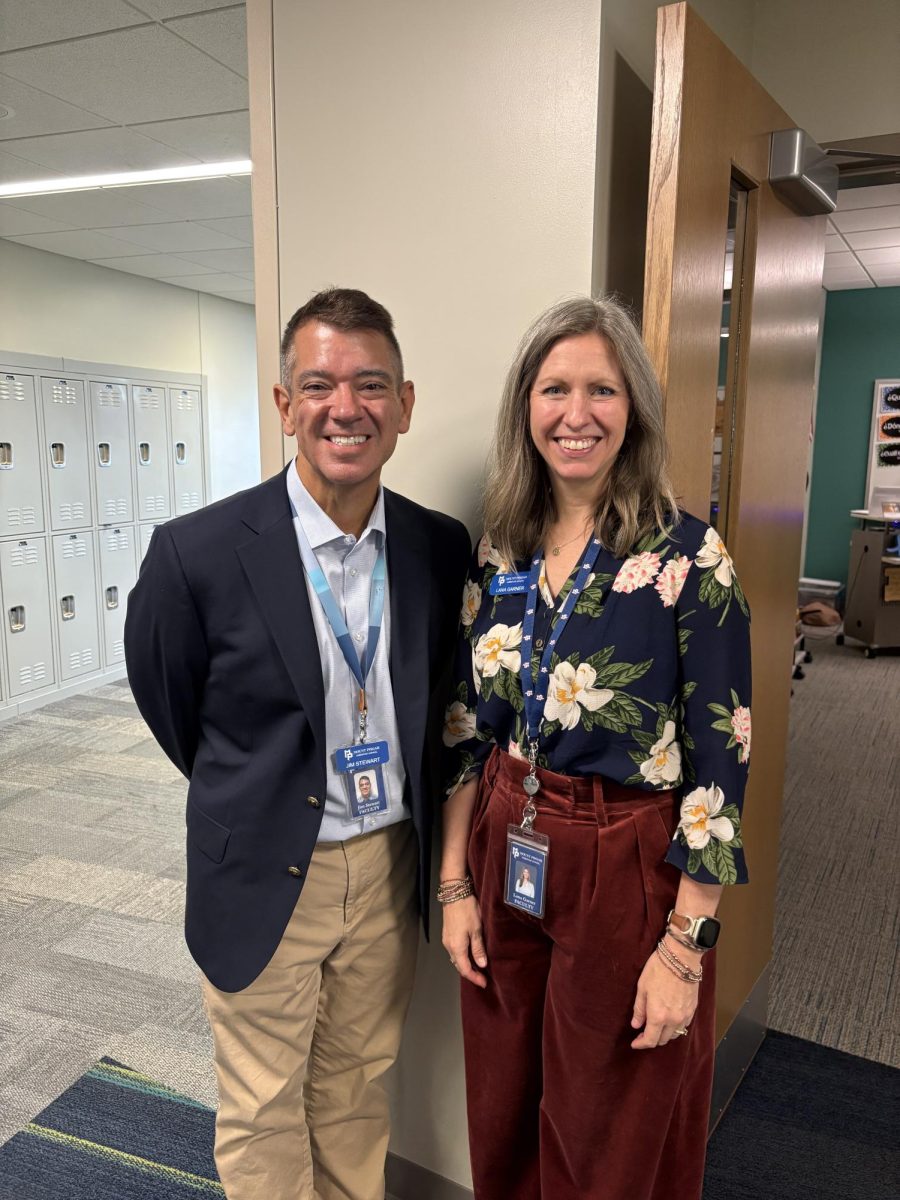

AI’s environmental footprint is garnering global and government attention.

Massachusetts Senator Marlkley and other senators introduced a bill to Congress that asked the federal government to assess AI’s environmental impact and create a standardized system for reporting future effects.

“The development of the next generation of AI tools cannot come at the expense of the health of our planet,” said Marlkley in a Feb. 1 statement to Washington.

The European Union approved its “AI Act” on March 13. The act will take effect next year and report on the energy use, resource consumption, and other impacts of AI systems, such as the foundation models that power ChatGPT, throughout their entire lifecycle.

These proposals focus on gathering information on AI’s environmental effects. Since AI is a relatively new technology, data on it is sparse and speculative. Companies can report on whatever they choose on the topic of AI impact. Data scientists currently do not have access to measurements of greenhouse gas emissions from AI.

As the world catches up with AI’s progress, more rules and standards will be established around it. When figures on AI’s environmental impact become public, scientists will be able to calculate definitive data and develop an actionable plan.

It will take transparency from companies, laws, and time to harness AI’s potential aid to the planet while also reducing its role in global warming, pollution, and other negative impacts.

Golestan (Sally) Radwan, the UNEP’s Chief Digital Officer, said, “There is still much we don’t know about the environmental impact of AI, but some of the data we do have is concerning. We need to ensure the net effect of AI on the planet is positive before we deploy the technology at scale.”